It may seem odd that I separately cover Japan (JP) in this survey of the trade movements of all major regions of the world. After all Japan ’s population is only 127 million (US Japan, however, is still presently the third largest economy in the world, and not long ago was the second largest economy, a title Japan held for more than 40 years, before China

As you will see, as the former second and now third largest economy, Japan Japan

Part 1, introduced the abbreviations, definitions, data bases and analysis methods used here.

Figure 1 presents JP’s total petroleum consumption rate (i.e., both domestic and imported petroleum) since 1980 as reported by the EIA or BP review (solid red circles and squares, respectively).

As you can see, JP’s petroleum consumption rate (solid red symbols) hit a peak in the mid 1990s at about 2.1 bby and has been slowly declining since them. By 2010, the consumption rate had dropped about 25 percent to 1.62 bby from the peak in the mid 90s. I will discuss the possible effects of Fukashima on Japan's petroleum consumption and import rates at the end of this article.

Figure 2 shows JP's total petroleum production rate (i.e., domestic production, solid blue circles and squares for EIA and BP data, respectively) and crude oil production (solid purple circles).

The 400 times smaller vertical scale of Figure 2 compared to Figure 1 should give you a sense of how little petroleum Japan is producing—only about 2-3 percent of its consumption. The BP review does not separately report production rates for JP because the rates are below its typical cut off of <0.1 bby, and so I set the BP production number (solid blue squares) for JP equal to zero. The EIA numbers (solid blue circles) show that there is indeed some production in JP albeit very small—between 0.04 and 0.05 bby for the last decade.

The purple circles, corresponding to crude oil production, are just slightly above the baseline. That is, crude oil production is almost negligible—less than 0.01 bby, and therefore of what petroleum JP produce, it is must be in the form of petroleum products; most likely products refined from imported crude oil.

Figure 1 also shows JP’s gross and inter-regional imports of total petroleum, crude oil and petroleum products. The EIA's import data (open circles) only runs from 1982 to 2009, while the BP review's import data (open squares) only runs from 2000 to 2010. The same applies to the export data in Figure 2.

As illustrated in Figure 1, total imports (open red symbols) are essentially identical to total consumption (closed red circles). Of course, this is just reflects the fact that Japan ’s total petroleum production is very small, and consequently, Japan

As illustrated in Figure 2, Japan

How is this possible?

Well, as also illustrated in Figure 3, the exports are exclusively petroleum products (open green symbols) and there are essentially no crude oil exports (open brown circles and squares). This implies that a portion of the petroleum JP imports (e.g., crude oil) is refined and then re-exported as a more valuable commodity (e.g., petroleum products).

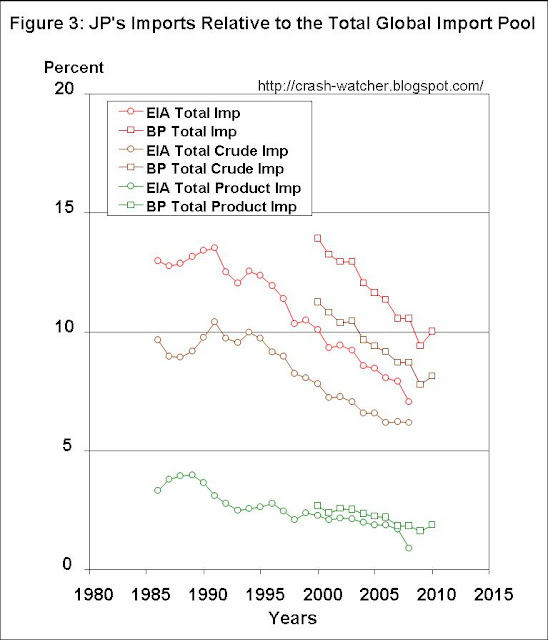

Figure 3 shows JP's total petroleum, crude oil and petroleum product imports relative to their respective gross and inter-regional global petroleum import pools. As usual the EIA and BP data set are separated because, as discussed at length, in other parts of this series (see e.g., Part 1 and Part 2) the EIA data-derived global gross export/import pool is larger than the BP review data-derived global inter-regional export/import pool.

JP’s total inter-regional imports (red open squares) are in steep decline from about 14 percent of the global pool in 2000, to 9.4 and 10 percent in 2009 and 2010 respectively. The decline in the proportion of the import pool going to JP is mainly due to the decline in crude oil imports—declining from 11.3 to 7.8-8.1 percent of the global import pool from 2000 to 2009-2010. Inter-regional imports of petroleum product imports have declined less steeply from 2.7 to 1.9 percent from 2000 to 2010.

Figure 4 shows JP's exports relative to the respective total gross and inter-regional global petroleum export pools, which, of course, is about the same size as the respective global import pool. This time there is not much separation between the EIA and BP data, possibly because the gross and inter-regional pools are so small.

The small vertical scale of Figure 4 compared to Figure 3, tells the main story: JP’s exports make up for less than 1 percent of the total global export pool.

There is a jump in JP’s inter-regional exports, from about 0.2 to 0.25 percent of the global pool during 2000-2006 to 0.75-0.7 percent during 2008-2010. As we will see (Figures 8 & 10) this recent increase in inter-regional exports from JP mainly goes to the rAP region and some to CH.

Comparing EIA and BP Export and Import data

Similar to the analysis of CH in Part 9, JP is a single country region, and therefore the gross (EIA data) and inter-regional (BP data) imports or exports, shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively, should not differ.

Figure 5 shows the differences between the EIA gross and BP inter-regional total, crude oils and petroleum product imports, which should equal the “intra-regional” values for these quantities, which in this case, for a single country region, should equal zero. Overall this seemed to be the case.

The difference for JP total imports (red triangles) ispretty close to zero (±0.1 bby) except for the -0.2 bby difference in 2009.

Figure 6 shows the differences between the EIA gross and BP inter-regional total, crude oil and petroleum product exports, which again, should equal zero.

The difference in total JP total exports (blue triangles) is indeed very small, and less noisy than the differences shown in Figure 5, no doubt because these are the differences between much smaller numbers than presented in Figure 5.

Trade movements of total petroleum between China

Figure 7 shows the specific quantities of petroleum, in units of bby, imported by JP FROM each of the eight other regions, and also shows the sum of JP's total inter-regional petroleum imports from all eight of the other regions (black "Xs"), which is the same as presented in Figure 1 (red open squares). Note these regional and total values are shown on the same scale.

It is very clear that the Middle East (ME) is where JP has gotten the bulk of its inter-regional petroleum imports over the last decade—with rAP a very distant second. For instance, of the total of 1.94 bby imported in 2000, 1.53 bby, or 79 percent, came from ME, and 0.31 bby, or 16 percent, came from rAP. In 2010, of the total of 1.67 bby that JP imported, 79 percent, came from ME, and 9.5 percent, came from rAP. Just visible above the "noise" in the figure from the other regions, for 2010 is 0.11 bby, or 6.6 percent of imports coming from the former

Figure 8 shows petroleum exports from JP TO each of the eight other regions and again, for reference, I show JP’s total exports (black “Xs” corresponding to the blue squares in Figure 2). Again, note the much smaller vertical scale of Figure 8 compared to Figure 7, illustrating that JP is a large net importer of petroleum. Also note that I don’t need a separate axis scale to portray the total exports versus regional exports, since they mostly go to two other regions.

As already noted in the context of Figure 4, JP’s total exports are a tiny fraction of JP’s total imports and total consumption, although in the three years the export rate, of petroleum products, has increased. Figure 8 illustrates that JP exports mainly to rAP and to China CH.

Figures 9 and 10 present the same data as shown in Figures 7 and 8, respectively, but expressing JP's petroleum imports or exports, to or from each of the eight regions, as percentages of the total global inter-regional petroleum import/export pool (global inter-regional imports and exports are the same). For reference, I also show JP’s total petroleum imports and exports as percentages of the total global petroleum import/export pool (“Xs” right vertical axis; again note the different scale in Figure 9).

Additionally, I have taken all of these data and made linear extrapolations of the 2000 to 2010 data (via linear regression analysis) out to 2021.

Figure 9, shows the major linear trend for declining total imports to JP (r2=0.96).

The linear regression coefficients for the prominent regional trend lines for declining imports from the ME (r2=0.98) and rAP (r2=0.91) are quite high. If the trend for declining imports from rAP continues, then by 2015, imports from this source will stop altogether. Other significant, but smaller in magnitude trends, include declining imports from CH (r2=0.81), and increasing imports from FS (r2=0.81). Imports from CH are predicted to end in 2011.

Figure 10 shows the weaker trend for the JP’s total exports to be increasing (r2=0.70).

Increasing linear trends of increasing regional exports from JP include rAP (r2=0.52), CH (r2=0.67) and EU (r2=0.80).

Figures 11 and 12 show the relative changes in JP's import sources and export destinations, respectively, as a percentage of the JP's total exports or imports in the years 2000 and 2010, and, as predicted for2021, from the linear regression trend lines shown in Figures 9 and 10.

As illustrated in Figure 11, despite the clear trend for declining imports (Figure 9), the ME remains the critical source of petroleum to JP. In fact its relative importance is predicted to increase, as the other former import sources, rAP and CH end. For instance, if the linear trends shown in Figure 9 continue, then by 2021, roughly 90 percent of JP’s imports would still come from ME, with nothing coming from rAP or CH.

The remainder of JP’s imports by 2021 would primarily come from FS, the one region showing a substantial trend for increasing import to JP.

Small that they are, JP’s exports trends, summarized in Figure 12, illustrates declining proportions of exports going to rAP and NA and increasing exports to CH and EU.

Summary and Conclusions

Of all the regions in this series, Japan

The Effects of Fukashima on petroleum imports

Some readers might wonder: will the total loss of nuclear power, due to the Fukashima disaster and the ensuing public response, cause Japan

The short answer is yes, it’s imports may increase somewhat, but not too much, because Japan

According to the EIA, citing “industry estimates,” fuel oil consumption could increase up to 238,000 bbl/d, or 0.087 bby, to provide electricity. That would correspond to about 5.4 percent of Japan Japan

Again according to the EIA, of the 1 billion kilowatt hours of electrical power it generated in 2008, 63 percent came from “conventional thermal sources,” 27 percent came from nuclear sources, with the balance from hydroelectric other renewable hydroelectric and other renewable sources. Of those conventional thermal sources, by far the bulk of electricity is from burning coal and liquid natural gases, both of which are also heavily imported. As explained by the EIA, Japan

Rolling blackouts in Japan Japan

-------------------

I am coming close to the end of this rather long series! Next time, I finish wrap up my regional analysis with a description of the remaining Asia-Pacific region’s petroleum Export and Import Trends.